Bitter Lake (2015)

An experimental documentary that explores Saudi Arabia's relationship with the U.S. and the role this has played in the war in Afghanistan.

Watch Trailer

Free Trial Channels

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

In other words,this film is a surreal ride.

All of these films share one commonality, that being a kind of emotional center that humanizes a cast of monsters.

There is, somehow, an interesting story here, as well as some good acting. There are also some good scenes

The storyline feels a little thin and moth-eaten in parts but this sequel is plenty of fun.

A young British woman lectures a room of Afghan students. 'Does anyone know what this is?' she asks, pointing to a photo of a urinal. 'An artist called Marcel Duchamps, who is very important in Western art, put this toilet in an art gallery about 100 years ago. It was a huge revolution.' This is one of many funny, unsettling and haunting moments in Adam Curtis' documentary, 'Bitter Lake'. His contention, explored 'through the prism' of Afghanistan, is that Western politicians frame complex events in simplistic terms of good and evil – a vision which reflects that of radical Islamism. As a result, he argues, the West has become 'a dangerous and destructive force in the world.'Curtis' own sparse narration is equally simplistic: a kind of 'Ladybird Book' treatment of Afghan history. His starting point is the 1945 pact between the USA and Saudi Arabia. This granted access to Saudi oil in return for US military protection and non-interference in Saudi society – a society permeated by a modern, extremist 'Wahabi' mutation of Islam. This aside, Curtis' story is not placed in a historical context. The strategic realpolitik behind the occupation of Afghanistan is neither explored, nor even hinted at. Instead, he takes at face value the stated intentions for the Western and Soviet invasions and documents the consequences that spiral from the willful blindness at their core. But the story is given nuance through the moments of archive footage he selects (much of it previously unseen) and the connections he draws between them – a device that subverts the familiar tale of 'liberation' and invites an uncomfortable reflection on Western attitudes and values.From the start, when an explosion splatters blood onto the lens, the film demonstrates how our cameras – ubiquitous, uninvited, invasive, 'embedded' – are also instruments of war. In one of the most excruciating scenes a TV journalist stage-manages the interaction between a man and his traumatised little daughter, who has just been blinded and maimed by a bomb. Why does he do this? To construct a 'heart-warming' story for us, the viewers back home. There are moments of rebellion too: a room full of women hide their faces from the prying camera with a book called 'Act English'; a man performs an impromptu martial arts routine directed, with smiles, at us; and in an extraordinary and moving sequence a young Mujahadeen fighter defies the camera and us, the watchers, with an invocation and a curse that draws on the land itself and Afghan sovereignty over it.Avoiding the 'continuity editing' that hails from Hollywood – in which a seamless flow of shots creates a story for the viewer to passively consume – Curtis uses instead the montage technique pioneered by the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. In this, the sequence of apparently unrelated images creates a 'dialectic' (conflict) which forces the viewer to create new meanings – meanings that are not contained within the individual images themselves. The scene of the young woman and the toilet is thereby informed by the footage that precedes it – a man being tortured, his head held underwater.One of the most chilling moments is a sequence where a soldier in full body armour collects 'DNA samples' from an Afghan villager, an image which recalls the work of the SS 'geneticist' Josef Mengele. Behind him another soldier pets a tethered goat. The contrast between the treatment of the animal and the person, unintended by the soldier who filmed it, is pointed and painful. In a later shot we watch as a British squaddie hidden in a ditch is entranced by a bird that comes and perches on his helmet, and this informs the moment with the goat. The interaction with the animals now seems to reflect a longing for a lost innocence: the innocence of a world in which 'we' are inarguably 'good'.The conclusion drawn by Bitter Lake is that British and American ignorance of Afghanistan meant that 'the West' was drawn into a complex Civil War with terrible consequences for the Afghan people. In this the film is hardly radical. But there have, Curtis argues, been unpredicted consequences for us, too, as there were for the Soviets. Our bloody interventions, so costly for the nations we invade, inevitably force us to question the very values our leaders claim to be exporting. In the process we are bought face to face with the vacuous nature of our own culture – a culture where 1% of the population own more wealth than the other 99% yet the placement of a toilet in an art gallery is described as 'a huge revolution.'

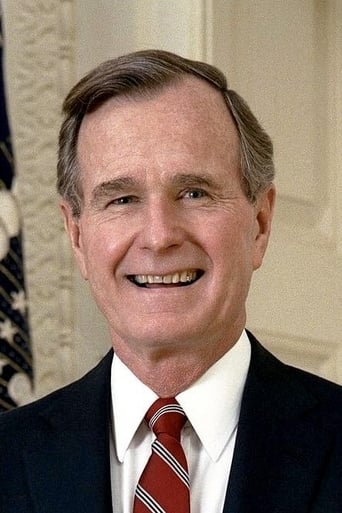

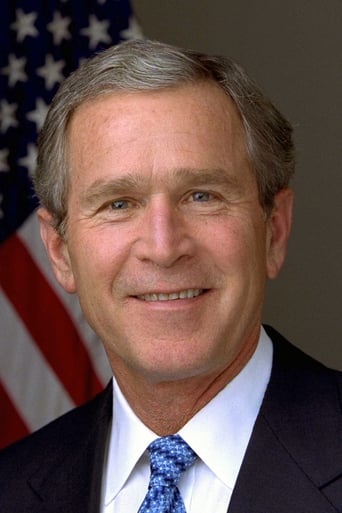

Bitter Lake is an ambitious documentary that begins with some promise. But I soon lost patience with it and after 40 minutes I stopped watching it. The ambition consists in the breadth of the perspective it adopts so as to illuminate how the mess that is contemporary Afghanistan, and in particular contemporary Helmand province, came to be. It locates the roots of this mess in deals at the end of WW2 that Roosevelt entered into innocently enough--perhaps naively even--with the monarchs of Afghanistan (modernisation via energy and irrigation from US built dams) and Saudi Arabia (modernisation by dollars exchanged for oil). Unsurprisingly, both monarchs were also playing local power politics that Roosevelt probably knew or cared nothing about: the former aiming to consolidate the control of his family and more generally that of his fellow Pashtuns at the expense of Afghanistan's other ethnicities, the latter to consolidate the control of his own family at the expense of radical Wahabists who were opposed to a modernisation that threatened to dilute, curtail or corrupt Wahabism. The intrinsic interest of such information is enhanced by fascinating original footage. Unfortunately Curtis ruins it all by eschewing the linear narrative that is essential to a clear presentation of such complex material so as to indulge in frequent cross-cutting without rhyme or reason back and forth in time and space; moreover, instead of weeding out images irrelevant to his narrative he revels in them. This technique works well for thrillers or for director-centred explorations of the auteur's mind. But when it is adopted in a documentary it just creates noise. What a pity!

Overall, as a documentary of American involvement in Afghanistan and its role as the power behind the 'throne' of Saudi Arabia it is overly long and of insufficient substance. There are many long sequences of essentially 'art house' material that does not drive the narrative. The actual narrative is no more than 15 minutes in length, and really that is well worth watching. Is it worth wading through more than 2 hours of 'found footage' for this narrative; for most people, I would say it's not. And that's probably why the BBC decided to release this only online on iPlayer. Even there it's not exactly very well promoted; the BBC's own iplayer search engine will not find it. It is still there but you have to use google to find out where it is. As to the narrative itself there are a number of fundamental flaws. The most important part of which is the importance and relevance of a British role in current affairs; there is a constant refrain of America and Britain, as if the two were somehow a joint force; that Britain somehow leads the way and America follows. It is Britain that industrialises and then so does America. It is British banks in which the Saudis kept their wealth, and it was this wealth that was then lent to people who could not pay it back, and the Americans followed along with this. In reality, it is Britain who has industrialised following its loss of empire, along with other previous European imperial powers like France. And it was British and other European banks that were bankrupted by wall street banks trying to shift their bad loans onto anyone foolish enough to buy them. Yes, a few wall street banks did go bankrupt but today they are stronger than ever. British banks are by contrast still bankrupt, kept alive by state ownership. Yes, there is the 'rust belt' in America where you can find disused factories but there is also 'silicon valley' which is a model of efficient production. In reality there has been a shift in the American economy which has led to decline in some areas and great wealth in others. And that shift is in some way reflected not in Britain in but within the European Union as a whole. Areas such as Britain are in decline but areas such as Germany, Denmark, and Netherlands have no empty factories and are very much in the ascendant.As for the political narrative that is superimposed onto events this is even more naïve. The image of 'good and evil', of 'liberating' foreign lands and bringing modern 'civilization' and technological progress to backward peoples is straight from 'empire'. The Americans don't really believe this because they quite plainly install corrupt undemocratic client regimes where they can and don't put serious money into improving the countries over which they have dominion. What Curtis is actually describing is the narrative of 'empire' where the British attempted to colonize much of the world including countries such as China and India; and where this did include huge investments to rebuild entire nations in the British imperial image, which was done under the narrative of 'modernization' and 'civilization'. America has always been careful in reflecting this narrative of 'empire' to the British to allow them the illusion of past glory. Curtis uncritically and unthinkingly reflects this back again, apparently unwittingly inwards to a British audience.Adam Curtis therefore makes fundamental errors in describing our own society. His narrative of Islamic society is much worse. Just as one example; to say the Osama bin Laden as a major influence in the Islamic world is just wrong. He was a member of a (tiny) militant offshoot of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, which was (and still is) led by Dr. Ayman al-Zawahri. Curtis knows this because he made a similar (and much better) documentary about 9/11 in 2004. The conclusion of that documentary was that 'al-queda' was an invention of the American intelligence and did not really exist. Here Curtis seems to forget the conclusions of his previous work and play into the conventional narrative put forward by Washington. Rather conveniently, it is all the fault of the 'extreme' views of the 'wahabis'. He draws a rather convenient thread from the extremists who brought the Saudi 'king' to power to the current target of an American bombing campaign in the middle east : Islamic State. Again, this does not in any way reflect the complexities of Islamic society in the middle east but rather a concern some in Washington have about their ally Saudi Arabia, on whom they depend on for oil. Who are Islamic State really? Surely Curtis would be aware of the small band of extremists who started in Mecca and Medina 1400 years ago and whose 'caliphate' within a few years threatened the gates of Constantinople, the imperial capital of the eastern roman empire. The greeks who ran the eastern roman empire had a great fear of these 'crazies' from the desert. Ironically the beliefs of these greeks stemmed from five centuries before this when another small band of 'crazies' threatened the roman empire; a band of extremist jews whose radical interpretation of Plato undermined the belief system of the roman world.

First documentary I've tried to watch that substituted actual narration for the insertion of random video clips and annoying background music. There's just enough narration in parts I guess for it to classify as a documentary, but the complete random selection of clips and music started to drive me nuts after a while.For example, "President Karzai's Motorcade" shows on the screen, followed by a lot of shooting and the aftermath. But it comes at a fairly random point, and there are no explanations, just UFO landing music in the background.Don't get me wrong, I lasted the whole thing and some of it was very interesting, but I got the distinct impression someone is touting for awards rather than a coherent narration.