The Thin Red Line (1964)

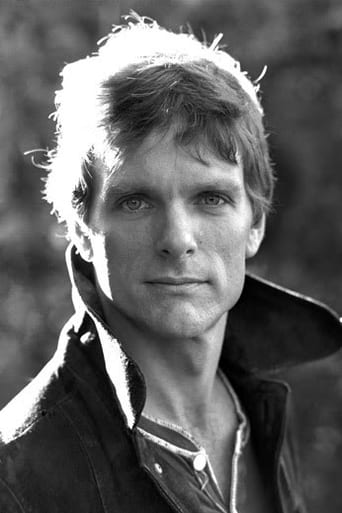

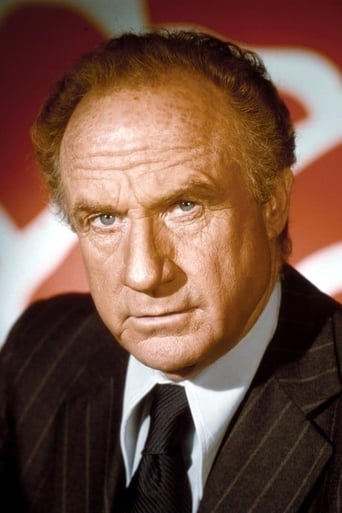

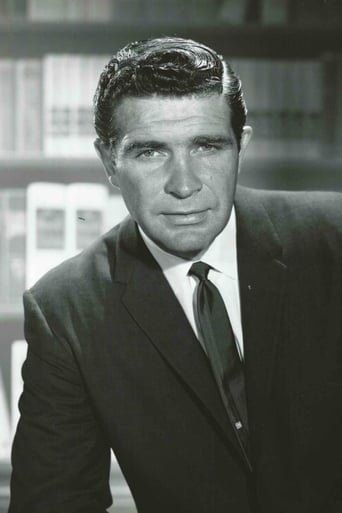

Set during the Allied invasion of the island of Guadalcanal in the Pacific theater during WWII, this film is based on the novel by James Jones. Keir Dullea is Private Doll, who dreads the invasion and steals a pistol to help him protect himself. Sergeant Welsh (Jack Warden), a caustic, battle-scarred veteran, hates Doll, whom he considers a coward. In battle, Doll kills a Japanese soldier and is filled with remorse, which further angers the sergeant. The next day, an emboldened Doll wipes out an entire enemy machine gun post and begins to feel as sadistic as Welsh. The two must work together to clear away some mines, but as they do, their platoon is surprised by a Japanese raid.

Watch Trailer

Free Trial Channels

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Truly Dreadful Film

It's a mild crowd pleaser for people who are exhausted by blockbusters.

Exactly the movie you think it is, but not the movie you want it to be.

There are moments that feel comical, some horrific, and some downright inspiring but the tonal shifts hardly matter as the end results come to a film that's perfect for this time.

James Jones also wrote "From Here to Eternity", and this novel has been filmed several times, last time in 1998 in colour, but the two versions compliment each other. This one is more stringent and poignant in its psychology and characterizations. Jack Warden and Keir Dullea clash from the beginning, they are both close to the thin red line separating sanity from madness, and they appear as rather half mad both of them, although Keir Dullea seems more liable, as he loses control a number of times. Jack Warden's madness is of a different kind, as he rather drives others mad than goes mad himself, and he is the better soldier of the two.It's about the critical battler of Guadalcanal, when more men were lost than even the Americans and theír ruthless colonel could afford. Although you don't see much of the Japs, the Americans didn't either, as the Japs were experts on ambushes and targeting Americans unawares, they appear as fearsome soldiers indeed. Many Americans have also testified, that Japanese soldiers were the bravest soldiers of all.It's a brutal and realistic war account from its worst sides, and if you can stand any amount of war atrocities, this is a film for you. If you can't, you had better stick to something nicer with dames. There are only two dames in this film, one in a short flashback, and the other one isn't even a dame, and her appearance is even shorter.

Titled after what one soldier says about there being only a "thin red line between the sane and mad", this World War II drama focuses on a young soldier who decides to distance himself as much as possible from his platoon's ruthless sergeant - a decision that gradually leads to him becoming a cold-blooded killer. Keir Dullea and Jack Warden are superb as the young upstart and sergeant respectively with an especially memorable final couple of scenes that capture just how unstable Dullea has become. Warden also has a touching bit in which he repeats his motto regarded dead soldiers ("it's only meat") in a new context. With none of the other characters fleshed out in any depth, one's appreciation of the film is likely to rest entirely on how much interest one takes in the dynamics between Warden and Dullea, which admittedly overshadow the historical backdrop and battlefield action. Edited with nightmarish flashback sequences and full of memorable dialogue (Warden warning of the dangers of letting his privates "start thinking" rather just following orders), this was though clearly intended as a less traditional war movie. As far as dialogue-heavy war movies go, 'The Thin Red Line' might have nothing on Samuel Fuller's masterpieces of the prior decade, but it deserves to be mentioned in the same breath at least as a film that taps into the psychology of war.

"A new motto: If you can't trans-cend, you might as well des-cend. I'm scoping out the bottom here....Mass, Density. Permanence. Finality. Termination. Rock. Even the word conveys heft, a certain assurance. No loss of focus here." – "Meditations in Green" (Stephen Wright)Film lags behind most other fields, mediums and art-forms, and so its no surprise that even over half a century after its release, few war films have been able to match the power of James Jones' novel, "The Thin Red Line".The second book in his WW2 trilogy, Jones' novel told the story of Charlie company and their participation in the battle of Guadalcanal. But what stood out about "Line" was the way it read more like a Vietnam precursor than a novel about WW2. Having himself fought at Guadlacanal, Jones had no time for the usual "greatest generation" and "noble war" fabrications. His novel was filled with drunks, cowards, thieves, sodomites, slackers, homosexuals and only occasionally heroes. His grunts battled mind-numbing tedium, fatigue, disease, nature, each other and their officers as much as they did the Japanese, and when victories were won, they were fairly meaningless. "It's just a fight over property," one character sighs.But for Jones, war was more than an overpowering injustice. His characters were separated into those who found themselves trapped in an indeterministic universe, wholly overwhelmed by circumstance, and those who turned war into a private struggle, a means of finding existential authenticity. This polarity is typical of war novels of the era, the theme of individuals as mere cogs in the war machine introduced by master authors like Dos Passos ("Through the Wheat" and "Three Soldiers") and Thomas Boyd and carried on in the works of artists like Norman Mailer, Joseph Heller, Stephen Wright, William March, and James Jones. Heavily influenced by post war existentialism, all these novelists offered only the faintest suggestion of hope for the individual.So beyond war, these artists used combat as an avenue to examine the plight of the individual caught up in and beleaguered by our twentieth century industry culture, the battlefield experience standing in for political and social cognition in our time. Norman Mailer's "The Naked and the Dead", for example, envisions a ruthlessly naturalistic world in which the so-called "rugged individual" is non-existent. Those who aspire to that state, such as Mailer's Sergeant Croft, are inevitably thwarted by circumstance. Likewise the heroes of William March's "Company K", Mailer's "The Naked And The Dead" and Heller's "Catch 22", all centring on characters trying to take a stand for personal, existential freedom against impossible odds. For these authors, free choice is not possible; we choose based upon economic necessities, upon psychic drives, or upon the indoctrination of our social upbringing.The intersection of this impotence with the impersonal, parasitic nature of warfare (war as a grotesque extension of the corporate/economic/political world), turns up again in Jones' own "The Thin Red Line", where the author has his characters Bell and Welsh see the individual as irrelevant and of little interest or worth to anyone but himself, whilst his characters Doll and Fife are shown to be nothing but a reflection of the opinions of others.But Jones always went further than trendy existentialism and one-note defeatism. What his novels did was set up oppositions, or opposing ideologies, and set them at war. Observe how he has one pair of characters embody different philosophical positions: for one soldier, if a human's actions are beyond his or her control, then the cause of war is irrelevant and inescapable. For the other, if war is a product of human choice, then three general groupings of causation - biological, cultural, and reason – can be identified and confronted.This method of philosophical investigation continues throughout the novel. Another pair of characters, for example, battle over whether or not war is ever morally justifiable. One symbolises war (or non-confrontation) from an ethical perspective – akin to St Aquinas' writings on "Just War" - while the other views war as an all-pervasive phenomenon of the universe. Such a description corresponds to a Heraclitean ("War is the father of all things") or Hegelian philosophy in which change (physical, social, political, economical, etc) can only arise out of conflict.Sandwiched between the WW2 masters and the next wave of great war novelists (Michael Herr, Neil Sheehan, Robert Mason, Philip Caputo, Gustav Hasford, Michael Maclear), director Andrew Marton's film adaptation of Jones' "Line" is an odd beast. It doesn't have the thematic weight or dramatic power of Jones' novel, but in the context of the other (mostly dumb) war movies released in the late 50s and early 60s, it's a remarkable film, an odd clash between grungy New Wave aesthetics, raw (not quite method) acting, and the stiff conventions of Old Hollywood. Unfortunately the film received little promotion and quickly faded into obscurity and is today mostly known for featuring an early performance by actor Keir Dullea.Decades later, "Line" would once again be adapted, this time by director Terrence Malick. Upon its release, many derided Malick's film for revoking or reversing the philosophy of Jones' novel, writers painting Malick as some kind of hippie spiritualist who turned war into a "natural", "poetic thing", a stark contrast to the cold, industrial and absurdist universe of Jones. Such a misreading is common, but not true.7.9/10 – Few war movies pass my BS-meter, but this one creaks through. These platoon movies tend to have a smallness – a myopia typical of a grunt's-eye-view - which is very unsatisfying, but Jones' writing is so strong, his lingo so beautiful, that Marton's flick is elevated by dint of sheer association. Even an auteur like Malick is massively indebted to Jones, some of the best moments and characters in his adaptation (Malick's cynical Sean Penn character even pops up in many of Jones' short stories – a surrogate for the writer) owing a lot to Jones' pen.

This version of James Jones' book follows the plot of the novel closely and actually received very high praise from the author himself. Jones wrote a letter to the director saying "Very rarely does an author get to write a letter to a filmmaker to say that he has captured the author's intention to the highest level possible." Jones was very pleased with the outcome of this movie, while the 1998 version heavily strays from his book. For example, Witt and Walsh in the 1998 version both quote a lot from another Jones novel, called "From Here To Eternity", and not from "A Thin Red Line". The main storyline, namely the clash between the Private and his Captain, is almost completely left out of the Malick film. In making the book into a movie, the 1964 film succeeds. Which is not to say Malick didn't create a riveting film in 1998, he just didn't really turn the book into a movie.