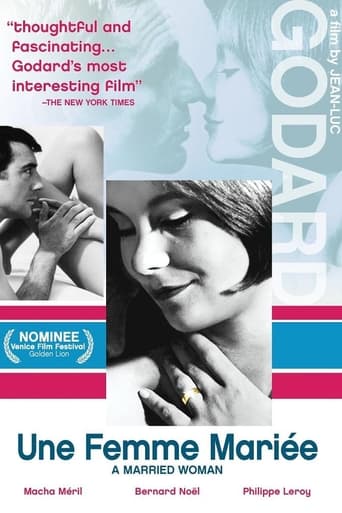

The Married Woman (1965)

A superifical woman finds conflict choosing between her abusive husband and her vain lover.

Watch Trailer

Free Trial Channels

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Wonderful character development!

Good concept, poorly executed.

Did you people see the same film I saw?

It’s sentimental, ridiculously long and only occasionally funny

To call Jean-Luc Godard's Une Femme Mariée a ponderous film is nothing short of the truth; the film, even at ninety-one minutes, is a lengthy, patient-testing endeavor. Yet, the film captures remarkable essences of mood and emotion that are nothing shy of poetic and quietly moving. Godard, once again, resorts back to classic, black-and-white film in order to accurately and wisely capture the sensual moods of the 1960's rather than become wrapped up in petty detail.This is yet another Godard film that will likely be appreciated by many after the film is over. When enduring the film, it becomes quite the challenge to stay in-tuned with it, since the prolific title-cards, frequent narrations, and sometimes uneventful instances seem to do everything they can in alienating and turning-off a viewer. However, after several hours (or, admittedly, days), contemplating a Godard film or keeping it in your head makes you warm up to its sensibilities and its techniques, as if you just cracked (or found yourself closer to cracking) the film's code.The film's plot is a sentence long, following the relationship between Charlotte (Macha Méril) and her lover Robert (Bernard Noël), despite having a relationship with Pierre (Philippe Leroy), as well with having a child with him in the process. Despite this setback, Charlotte still spends much of her time with Robert, doing typical things you'd find in a Godard movie; whispering softly, discussing philosophy, getting romantic, and simply enjoying the presence of each other.Once you get past the fact that the film is stripping everything you'd expect it to include down to very minimalistic ingredients is when your response to Une Femme Mariée may be a bit stronger or perhaps simply unfazed. The film is a film of essences, atmosphere, tone, and emotion, captured in black and white to only affirm its details are shifted out in favor of a less-distracting experience. Throughout the film, we see Robert and Charlotte show affection for one another and also admire their own bodies. Of Godard's French New Wave films that I have seen up until this point, Une Femme Mariée is the one that contains the most controversial imagery (by American standards) in terms of nudity.Yet, Godard's film is certainly not graphic by any means; by American censorship standards even in the present day, it's incredibly tame, mostly using lengthy close-ups to depict pasty-white skin. By doing this, Godard creates a very intimate and sexual mood, a common characteristic of the 1960's in France, again, catering to the idea that he favors capturing an essence or a mood rather than focusing on plot-progression and intense character development. This sexual atmosphere is surprisingly not arousing but more tender and appreciative of human anatomy, something we're sometimes believed we are not supposed to be proud of.In the regard of being a meditative, moody little drama with some raw feelings of emotion and intimacy, Une Femme Mariée does succeed and meshes nicely with Godard's other New Wave films. However, the picture does become watery and difficult to sit through, especially during the third act when things seem to take a more ambiguous road. Expect Godard, receive Godard, what you do and think after may vary.Starring: Bernard Noël and Macha Méril. Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard.

He did it in 1961, in 1962, in 1963, and in 1964 Godard made another movie about a woman questioning the meaning of love, life, and acting. This movie, like the others, is a fun treat for Godard fans and fans of inventive camera and editing techniques, though it doesn't have as much heart as "Contempt", "Une femme est une femme", or even "Vivre sa vie"."Une femme mariee" depicts the affair of a bored housewife, but director Godard strives to convey the feeling that we are reading about her in a women's magazine. To achieve this the scenes with the actors abruptly cuts to fashion photos, make- up ads, and text. It's a stylish movie with a brisk pace, but, just like a magazine story, it doesn't take long for it to leave the mind or heart either. Yes, Godard's creativity may soar higher here than ever before. His playfulness leaps through the surprising angles and reveals, his panning of words in magazines, x-ray photography, and whispered narration, etc, yet the story seems tacked on. We float from idea to idea as they enter and leave the director's head, which is fun for a one-time viewing, probably the way that glancing at his sketchbook may feel, but the lack of motivation, of purpose, inevitably keeps this effort from standing in the same grouping as the previously mentioned works, the ones that we watch more frequently, the ones that give us cinematic nourishment, the more organic, more well-rounded, fully realized pieces.

We see a hand, then another hand, in the frame of the opening shot of Jean-Luc Godard's Une femme mariee. It's from here that we see a succession of images, all of the body but never anything explicit- a leg, a belly-button, hands, a back, a nude front but covered breasts. Godard is inquiring about the form of a body in and of itself while also trying to find new ways of photographing it. In these shots, which also happen again in this sort of physical poetry a couple of other times in the film, illustrate something both absorbing and elusive about the film in general. It's about form and 'lifestyle, of the married life and the affair, of a bad husband and a tricky squeeze on the side... but then we also have scenes that puncture through the infidelity drama: there's a scene where Robert, the lover, and Charlotte, the main femme of the movie, are sitting in a movie theater at an airport, discreetly, and one wonders what they're about to watch (just before this an image of Hitchcock appears as if Charlotte sees it in the lobby), and it turns out to be some kind of holocaust documentary ala Night & Fog. They leave right away. Too much of a shock, or too much reality? How does the outside world affect these people?We get a lot of scenes of characters just talking to one another, asking questions, sometimes in documentary form. Whether it's really Godard off camera asking the questions and turning it into a docu-narrative of some sort (the old Bazinian logic taken to an extreme that an actor in front of a camera is still in a documentary of the actor acting on camera perhaps), or the characters themselves is kept a little unclear. But this doesn't distract from the dialog and monologues being generally, genuinely intriguing and moving even. There's one scene in particular that I shall not forget easily, no pun intended, when Pierre, the husband, espouses about memory and how "impossible" it is for him to forget, and how rotten it can be for someone who has dealt with real horror (he recalls a story, as his character is a pilot, of talking to Roberto Rossellini about a concentration camp victim and memory and that it made him laugh - again, a very harsh contrast of Dachau and Auschwitz mentioned for interpretation). This and a few other times when characters just go off on something has a lasting impact. Une femme Mariee is filled with the sort of cinematic rhythm that would immediately say to someone unfamiliar with foreign/art-house film, let alone Godard, "oh, that's an 'arty' movie". It certainly is: everything from its themes of alienated characters to its lyrical and original cinematography to the repetition of the Beethoven music (later used in Prenom Carmen) to image itself becomes an issue like when Charlotte obsesses over ladies wearing bras in a magazine, it's all from an artist who expresses his concerns in a my-way-or-the- highway attitude to the audience. And you want to go along with him, if curious enough, to see where he'll take his trio of characters in the Parisian settings. Sometimes there's even weird, dark humor, like when Charlotte finds a random record of some woman in agony and it's the sound of a woman just laughing - something that Charlotte and Pierre listen to in silence until Charlotte wants to put on another record and she becomes like a little kid trying to put it on without Pierre getting in her way. What looks disjointed and without a plot is deceptive when looking at it in pieces. But somehow Godard's film works as a whole piece, and it's part of the point to find this character Charlotte not easy to figure out. The men in her life barely know themselves. And by the end, when it should be about the melodrama of a baby on the way, Godard side- steps this (already dealing with it comically in A Woman is a Woman), by making it about something else on the surface and underneath full of tension. Notice how demanding Charlotte is of answers from Robert about what it means to be an actor. He answers well and stands his ground, but it becomes noticeable that it's not about getting answers on acting or real love but about this woman's tortured self-made life. It's not emotionally gripping, but it gets one to think and it's this that makes Godard's film special in his cannon of great 1960's works.

This time there's one female lead choosing between two men, something pretty rare in a medium usually fueled by male fantasies. Charlotte is a young middle-class married woman having an affair with an actor. She has promised her lover she'll divorce her husband, but an unplanned pregnancy makes her question that decision. The film follows her as she attempts to decide between them.Like other Godard films that followed it (Masculin/Feminin, 2 or 3 Things, Made in USA) one of the primary themes here is the extent to which a modern individual's life is manipulated by commercial culture, and how it influences the choices we make. Perhaps because he had yet to fully mature as a filmmaker, this theme is much less subtle here than in those later films. Charlotte is barraged with nonsensical beauty ads and Cosmo-type articles about achieving the "perfect breast size," and in one famous shot is literally dwarfed by a billboard of "the perfect woman" in a bra. The height of social control is reached in the form of an absurd device her lover gives her that hooks around her waist like a belt and sounds an alarm every time her posture slackens. The effect of this visual over-stimulation on her is pernicious. Like the magazine ads we're shown, her thoughts (heard in voice-over) are fragmented and incoherent, indecisive and ultimately meaningless.The other recurring Godardian theme appearing here is the commodification of the female body. To her bourgeois husband, who represents the patriarchal tradition and middle-class status quo, she's more an object to be protected (like the records he brings back from Germany) and exploited (he rapes her when she won't make love) than a human being to be understood. Ironically, his unwillingness to forgive a past infidelity and his possessive jealousy only compels her more to see freedom in a lover. But unlike her husband, who treats her like a commercial object, her lover treats her as a sex object ("Is it still love when it's from behind?" she wonders early in the film) and seems interested only in her body. Her scenes with him are composed of tightly-framed shots of his hand stroking her naked body, shots resembling the photographs selling stockings and bras in her magazines. Her lover literally sees her as a whole person only once, when she goes up on the roof naked. Accordingly, he gets angry, out of possessiveness. Godard's dim view of the condition of modern woman sees her as unable to break free of her past (her husband) due to the self-sufficiency and humanity she's denied in the present. As she ages, a woman's role goes from sex object to status-based commodity, and society teaches her that to think otherwise is wrong. This is a concept still ahead of its time today, when violent, over-sexualized junk like the Tomb Raider movies are sold as female empowerment.As with most of Godard's films, there are always several things going on at once, and this capsule review barely scratches the surface. In the context of his career, the film is best understood as an early version of 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, which he made three years later and is unquestionably better. By that film, Godard had learned to synthesize his social, emotional, and political themes into one seamless whole, discarding the artificial narrative conventions that serve him no purpose. This one, while no classic, is essential viewing for anyone interested in Godard's progression from brilliant filmmaker to serious artist.