The Cow (1969)

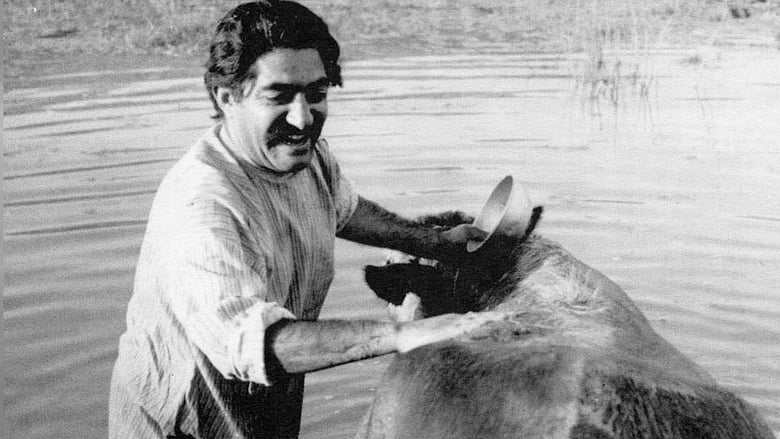

An old villager deeply in love with his cow goes to the capital for a while. While he's there, the cow dies and now the villagers are afraid of his possible reaction to it when he returns.

Watch Trailer

Free Trial Channels

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Just what I expected

This is a tender, generous movie that likes its characters and presents them as real people, full of flaws and strengths.

The film creates a perfect balance between action and depth of basic needs, in the midst of an infertile atmosphere.

The thing I enjoyed most about the film is the fact that it doesn't shy away from being a super-sized-cliche;

Nearing the end of ICM's best of 1969 movie poll,I searched for a final title to view. Seeing a post by fellow IMDber OldAle,I was excited to read praise for an Iran New Wave (INW) title, which led to me going down to the farm.View on the film:Farming closer to the Neo- Realist movement than the French New Wave, writer/director Dariush Mehrjui & cinematographer Fereydon Ghovanlou give the village a dour appearance,where the subtle use of black and white shadows lining the streets reflecting what lays at the dark heart of the village. Lovingly following Hassan's feeding of his cow, Mehrju and Ghovanlou take all that Hassan holds dear with flickering camera moves snapping Hassan's breakdown. Dipping into the dark human horror which would be explored the same year in the Czech New Wave film The Cremator, Mehrjui whips Hassan with inhumane treatment from the the locals, captured in frenzied dissolves, fading to the overlooking figures in a landscape.Born from Gholam-Hossein Saedi's play,the screenplay by Mehrjui features the most prominent edge from the Iran New Wave (INW) via Mehrjui dissection of the greed and pettiness followed by all of the rural locals, with the thought they show towards giving Hassan the bad news,burning into vile outbursts as Hassan's mental state degrades. Becoming completely separated from the villagers, Ezzatolah Entezami gives an incredibly expressive performance as Hassan,whose breakdown is treated with a gradual, earthy realism by Entezami,as Hassan looks in hope of seeing the cow on the field.

1953. The United States, the United Kingdom and their respective corporate cartels stage a coup and successfully overthrow the democratically elected government of Iran (specifically Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who was set to nationalise local oil). Enter Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, your classic dictatorial, Western puppet leader. He's a full blown oil pimp. His people hate him, but the West love him. He rules as Shah of Iran until 1979, at which point he is overthrown by a local revolution led by the religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini. The rise of Khomeini is presented as a populist and spontaneous uprising, but Khomeini was backed by both the US and UK with the specific aim of ousting Pahlavi, a one time puppet who, like Saddam Hussein, had grown too big for his boots. Prior to his ousting, Pahlavi had begun to flex his muscles, refusing to sign away exclusive oil rights and beginning a programme to seek "oil-sales policy independence". The oil barons and superpowers don't like this. They stage another illegal coup. Not wanting left-wing democrats taking over from the Shah, the CIA began courting the Muslim Brotherhood and the Ayatollahs, all essentially religious fundamentalists. These clandestine operations echo CIA orchestrated coups against democratically elected officials in Guatemala, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Cuba etc etc (see Alex Cox's "Walker"), most of whom were trying to institute land reforms, nationalise resources or help bridge the gaps between the peasantry and landowners. Can't have that.Shortly prior to the toppling of Reza Pahlavi, a "soft war" was waged against Iran. The West refused to buy Iranian oil, began a campaign of economic pressure, planted covert agitators to fan religious discontent, put embargoes in place, staged oil and banking strikes and began cynically protesting the presence of "Iranian abuses of human rights". Meanwhile, Ayatollah Khomeini, who was being groomed to be the new leader of Iran, began appearing on news networks, which willingly gave voice to his propaganda. The message was clear: Anglo-American intelligence was committed to toppling their puppet. The Shah fled in January, and by February 1979 Khomeini had been flown into Iran to replace the Shah's government and proclaim the establishment of his own repressive theocratic state. Almost immediately, the US then began funding Iraq's decade long war against Iran.Over the years, leaks and whistle-blowing would reveal the point of the Iranian fiasco: the radical Muslim Brotherhood movement behind Khomeini was endorsed specifically in order to promote the balkanization of the entire Muslim Near East along tribal and religious lines. In encouraging autonomous groups it was hoped that chaos would spread in what was termed an "Arc of Crisis", which would spill over into Muslim regions of the Soviet Union. Of course such arrangements never go quite to plan, but then, chaos partially was the plan.Iranian art cinema was born in 1962 with "The House is Black", a documentary by Farough Farrokhzad which revolved around a leper colony. From here the Iranian New Wave's compassionate, neorealist and "humanist" qualities would spring. Seven years later Dariush Mehrjui's "The Cow" was released, regarded by many as the first "true" feature film of the Iranian New Wave. The film was funded by the Shah's government but was then quickly banned by the Ministry of Culture, presumably because it dared portray the impoverished conditions of rural Iran (ironically, after brutally oppressing his people, the errand-boy Shah was granted freedom and citizenship in the United States). In 1971 the film was smuggled to the Venice Film Festival, at which point it gained considerable recognition. Thanks largely to its odd and ambiguous plot - which plays well to Western audiences unfamiliar with Iranian culture, history and customs - the film raced across the world."The Cow's" plot? Dark, allegorical, mysterious and twisted, the story revolves around an Iranian villager, played by Ezzatolah Entezami, who owns the only cow in his village, a village perpetually terrified of thieves and invaders. After a brief absence, Ezzatolah returns home to find that his cow has died. This event plunges the man into madness, such that he eventually comes to believe that he is himself a cow.The film plays like a cross between Kafka, an old folk-tale and the neorealist movement (neorealism is almost like a rite of passage which nations must at one point pass through). Of course those familiar with neorealist works may find little of interest here, but "The Cow" was nevertheless daring in its depiction of rural poverty in a society where the ruling class enjoyed all the fruits of economic growth. With its modernist score and bovine metamorphosis, the film also has an unsettling quality, particularly in the way it portrays a man whose identity, work, income, life and happiness are so inextricable from his beast of burden, his property, that its absence instigates an almost immediate and total meltdown. Our hero isn't just close to his one earthly possession, he seems to embody it before its absence. Elsewhere the film points fingers at scapegoaters, blind religious faith, jealousy and the dangers of suppressing truths. Incidentally, one of the chief chapters in the Koran is titled "The Cow", and like this film deals with "those who cover up reality" and the way "denial leads to disease". In that story, a cow's death is responsible for deciding who is guilty of a crime. Here, it's almost as though Ezzatolah becomes the cow to prevent crimes being forgotten. Unsurprisingly, the film was written by Gholam-Hossein Saedi, a staunch Marxist. The plot loosely (but not necessarily) echoes Marx's writings on "animal-like, estranged, objectified human labour".Aesthetically, Mehrjui stresses flat planes, windows, squares, frames, screens, and frequently has his characters arranged like we the audience, looking in as Ezzatolah's grotesque transformation takes place. The film has a creepy, primitive quality; like a folk tale re-enacted by a gang of centenarians.8.5/10 - Worth one viewing.

This simple tale is open to interpretation, which can be considered positively or otherwise it perhaps hearkens back to folk tales which are passed down orally, and contain simple plots which are then the basis of discussion. In this way it is easily remembered and its meanings can be deciphered afterwards by those who watch it. However it also means that the film seems overlong for the most part, pre-occupied with repeating sequences and behaviour again and again, and even drawing out the fairly dramatic ending which arguably diminishes its strength. Perhaps it would have been better presented in a shorter runtime, or a more heavily stylised manner such as that of the title sequence. Nevertheless, regardless of enjoyment there are many threads of discussion that can be considered.One of the key questions raised by the film is that of the mental stability of the protagonist, Hassan, whose loss of his animal will bring about his somewhat metamorphosis into the same creature. At the start of the film he is seen behaving extremely strangely as he leads his cow back to town, exultantly dancing around it as he washes and caresses it. This man is not behaving as the other people (such as the children) do. Hassan is mirrored somewhat by the town idiot, who is berated by the other people, and even locked up so as to keep Hassan himself from learning the secret of his cow's death. This mirroring, and Hassan's transformation, make it possible to consider the village's relationship to both Hassan and his cow certainly throughout neither are treated with respect, and the film's end highlights this.Perhaps Mehrjui, the film's creator, comments on the actual importance of the cow and this man's relationship, an idea that is supported by the title of the piece.

While it's director went on to do better work and this film marks a return of cinema to the post Shah Iran, sitting through it is an effort.We lose out both ways with the basic technique and unshaded characters of underdeveloped cinema (this one is like an early Yilmas Guney but nowhere near as good) made pretentious by what we must assume is opaque symbolism on the Kafka model.This village overfills it's quota of idiots.Best thing is the title background of the man walking a cow, reduced to an abstract.