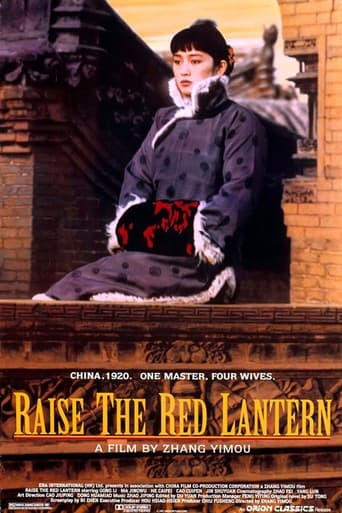

Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

In 1920s China, a nineteen year old Songlian is forced to marry the much older lord of a powerful family and compete with his three wives for his attention, slowly uncovering the dark truths that lie within their gilded cage.

Watch Trailer

Free Trial Channels

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Memorable, crazy movie

An action-packed slog

A bit overrated, but still an amazing film

Story: It's very simple but honestly that is fine.

I loved this film. It flows like reading a beautiful book. Well directed and perfectly acted.

Raise the Red Lantern is masterful piece of film history.A bleak tale of sexual subjugation and ruthless scheming in a single opulent household in 1920s China, Raise the Red Lantern portrays four women locked in struggle for attention from the master of the house, who every day favours one of his concubines with special honour of spending a night with him. And as usual among the hereditary nobility, the highest achievement is pregnancy resulting a male child.The tense plot is perfected by the backdrop of suffocating ancient mansion built out of dull bricks and adorned expensively with etchings and drapery, and staffed with servants. The watcher barely gets a glimpse of the outside world as if nothing even existed outside the walls of the compound where the women are imprisoned in concubinage. And almost as faceless is the master himself, whose face we never see in close up shot.Cinematography and set building stand out as excellent, with stark reds of the drapery and lanterns, contrasting with the muted greys of the mansion itself, later covered by a blanket of snow.

Raise The Red Lantern demonstrated the importance of Chinese cinema. Luscious use of colour, photography and setting it in the past meant you could use symbolism to make coded criticisms of China today without or hopefully not raising the eyebrow of the censor.Our protagonist Songlian is a 19 year old woman in 1920s China, beautiful and educated. When her father dies her step mother sells her as a concubine to her wealthy master. She is the fourth mistress and when the red lantern is lit outside her house, it signifies that the master will spend the night with her and she will be treated royally.The master has four wives, the first is older, maybe around his age and she has bore him a child but is largely forgotten. At her age she knows she cannot arouse the interest of the master.The film is almost soap opera like as the other wives compete for the interest of the master and this means conspiring, being petty and mean. It leads to tragic results and Songlian distils that this is a game where the women cannot win. As the wives get older the master will find a younger model with something different that interests him. She retreats into solitude.Director Zhang highlights the lack of power women had in the past in this Confucian orientated society but also shows what could happen to you if you did not play by the rules in an archaic system.

This is a very brief review of "Red Sorghum" (1987), "Ju Dou" (1990), "Raise the Red Lantern" (1991), "The Story of Qiu Ju" (1992) and "To Live" (1994), five films by Zhang Yimou. Each film stars actress Gong Li, each works as a companion-piece to the other, and each deals almost exclusively with the oppression of women within early 20th century China.Zhang's debut, "Red Sorghum" stars Gong Li as Young Nine, a peasant who is sold to a wealthy leper. Things only get worse for Nine, who must fend off a series of rapists, mean men and the Japanese Army itself, all the while running a successful winery. Throughout the film, Zhang uses boxes, deep reds and tight squares to amplify Nine's sexist surroundings. Indeed, the film opens with Nine literally forced into a box, a social reality which she spends the film attempting to break free of or even transform. For Zhang, China wasn't "disrupted" by the Japanese invasion, it was hell long before. Like most of Zhang's films during this period, "Sorghum" sketches the cultural and socioeconomic conditions which spurred China, with hopeful arms, toward Maoism.Zhang's next film, "Ju Dou", covers similar material. Here Gong Li plays Ju Dou, a woman sold to a violent oaf ("When I buy an animal I treat it as I wish!") who owns a fabric dying establishment. After her husband is crippled, Ju Dou forges a relationship with Yang Jinshan, a relative. When Ju Dou and Jinshan have a child together, the kid grows up into a mean brute. Like "Sorghum", "Ju Duo" is a tragedy obsessed with rich reds, boxes and patriarchal violence. Whilst its plot superficially echoes Zhang's own adulterous, then-scandalous affair with Gong Li, Zhang seems more interested in the way Ju Dou and Jinshan hide their illicit affair from other villagers. For Zhang, the duo's tacit submission to social mores merely validates the notion that their love is scandalous and so merely validates the symbolic power of the crippled patriarch, a power which Ju Dou's son must – as per his mother's very own actions – thereby respect and avenge.The arbitrary nature of power, and how this power is always "symbolic" and always unconsciously maintained (via ritual, personal belief and shared delusions), is itself the obsession of Zhang's "Raise the Red Lantern". Here Gong Li again plays a woman sold to a wealthy man. This man has several other wives, all of whom begin to violently fight one another in an attempt to win the patriarch's adoration. "Is it the fate of women to become concubines?" a character asks, pointing to the film's deft critique of feudal relations. Zhang's first masterpiece, "Lantern" is again obsessed with reds, boxes and sequestered women, though here Zhang replaces the voluptuous colours, camera work and widescreen Cinemascopes of his previous films with something more restrained. Because of this, Zhang's conveying of claustrophobia and oppression, of mind and spirit pushed to madness, feels all the more powerful.Next came Zhang's "The Story of Qiu Ju". A near masterpiece, it stars Gong Li as Qui Ju, a peasant farmer who embarks on a quest to avenge her husband, who's had his crotch kicked in by a village leader. More emasculated by this attack than her own husband, Qui Ju's quest takes her all across China, dealing with a Chinese bureaucracy which seems quite helpful, polite and even rational. And yet still this bureaucracy does not please Qiu Ju. It thinks in terms of commodities, monetary recompense and punishment, whilst Qiu Ju (like Zhang Yimou himself, whose previous films were banned, without explanation, by Chinese authorities) seems more interested in acquiring a "shuafa", a simple explanation and apology. By the film's end, both the "primitive justice" of rural China and the "civilized justice" of modern China are simultaneously mocked, praised and shown to be thoroughly incompatible. Zhang's first "neo-realist" film, "Qiu Ju" was shot with hidden cameras, amateur actors, and so is filled with subtle observations, cruel ironies and beautiful sketches of peasant life.One of Zhang's finest films, "To Live" followed. It stars Gong Li as Jiazhen, the wife of a wealthy man (Ge You) who is addicted to gambling. When this gambling results in the family losing its mansions, riches and status, Jiazhen and her husband are forced onto the streets. Ironically, this set-back saves the family; the Cultural Revolution arrives, and with China's shift to nascent communism, all wealthy land owners are demonised, attacked and killed.Unlike most films which tackle life under Mao's Great Leap Forward, "To Live" carefully juggles the good and bad of what was essentially a nation shirking off feudalism, monarchs, uniting and then trying, clumsily, to cook up some form of egalitarian society. This quest results in all manners of contradictions and socio-political paradoxes: community, solidarity and a simple life save our heroes, but their world is one of paranoia, danger, and in which everyone and everything is accused of being "reactionary". The film ends with Jiazhen's daughter dying, a death which is the result of both unchecked consumption (a doctor dies gobbling food) and communist "reorganisation" (all competent doctors have been killed/jailed for being counter-revolutionary). This jab at communism got the film banned in China (further highlighting the insecurity of the regime). Ironically, Maoism saw massive positive health care reformations, and saw an improvement in mortality rates which at times surpassed even then contemporary Britain and parts of America (life expectancy doubled from 32 years in the 1940s to 65 years in the 1970s). But such things don't concern Zhang. Spanning decades, "To Live" is mostly a broad account of life, love, loss and growth (the personal and political), all unfolding upon a canvas that is devastatingly cruel. Significantly, the film's title is both adjectival and a command; this is "what life is", but one must nevertheless "always push on". Gong Li and Ge You in particular are excellent.8.5/10 - See "Black Narcissus".